Every now and then, a book comes along that completely changes the accepted paradigm. Sex at Dawn by the anthropologists Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jetha, published in 2010, is such a book.

Earlier, the accepted wisdom was that primitive people, our forebears, pair-bonded for life, the males being vigilant in fending off other males in order to ensure that any children that ensued were his own. The book The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins, helped popularize this view. A female traded sexual access to gain the resources the male provided, and prehistoric society was basically monogamous.

Sex at Dawn posits an entirely different early history, one in which early humans were basically promiscuous. One may wonder how anthropologists can reach reach any conclusion at all about the sexuality of primitive humans who left no record of their sex life, but the authors are very convincing. They examine the conduct of chimps and bonobos, our nearest genetic relatives; the behavior of present-day indigenous people; and the sexual response of modern human beings to reach their radical conclusion.

Our nearest genetic relatives are chimps and bonobos. These great apes, who share more than 98.7% of their DNA with us, are known to engage in frequent sex with many partners. Bonobos in particular are famously promiscuous, using sex as a social glue, much like a handshake. Sometimes males have sex with males and females with females; it all keeps the tribe happy and bonded together. Talk about the pleasure principle!

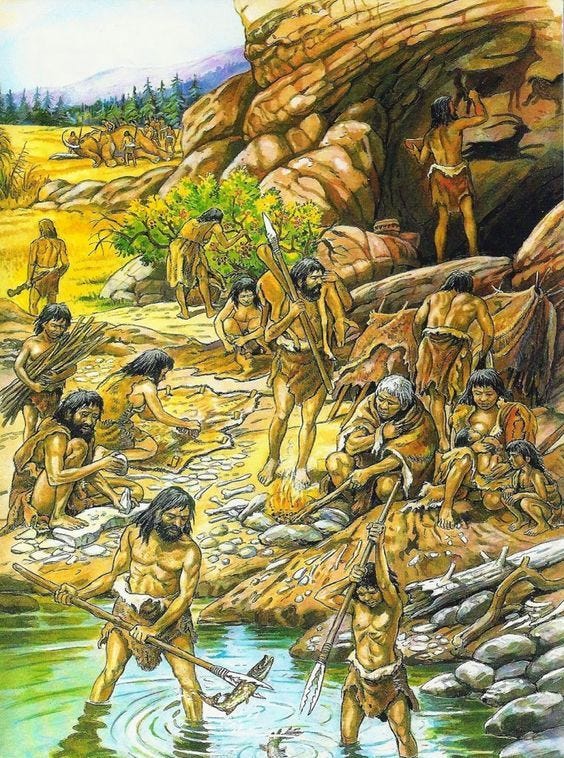

For hundreds of thousands of years, before the discovery of agriculture some ten thousand years ago and the beginning of property ownership, humans organized themselves into nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes. Similar tribes around the world exist to this present day, and anthropologists have been able to observe how they live. In such tribes, everyone works together and sex is frequent and casual. Some people pair off for a while, but most people have several partners at any one time. Paternity isn’t an issue; there isn’t any property to pass on; and children are raised by the entire tribe.

Finally, Ryan and Jetha point to sexual response in humans today. Both a woman’s delayed orgasm (relative to a man’s), and her capacity to have more than one orgasm indicates that in prehistoric times, she might well have enjoyed mating with one male after another. The theory of “sperm competition,” with only the most robust sperm penetrating the egg, says this sexual behavior conferred a genetic advantage to the tribe.

What does all this mean to human beings today? Perhaps it helps explain the fact that more than half of all American marriages end in divorce and that extramarital liaisons persist in every culture. The authors declare, “The assertion that human beings are naturally monogamous is not just a lie; it’s a lie most Western societies insist we keep telling each other.” Perhaps the desire for sexual novelty is fundamental to human nature and can never be eradicated. Perhaps we should not be so quick to condemn the occasional affair, which need not end the marriage.

We do not live like prehistoric people, and there’s no reason to think we should do so in this regard. But understanding how our forebears probably lived should make us more tolerant of those who break sexual boundaries today. These sensual outlaws may well be reverting to a primordial past.

Some options diminish as we age, but were you younger and single, you might find more accommodating mates. Welcome to The Pleasure Principle!

Thank you for another informative read, dearest Cathy...(o: