Ah, the pleasure words provide! The joy of romping through a language meadow and collecting flowers and grasses! Finding the exact word for what you want to convey is one of the great delights of writing, or speaking.

Poets and poetry readers especially relish words and phrases—the shape of them in the mouth (saying “simulacrum” is like chewing gum), how they sound in the air —but poets aren’t the only ones.

Perhaps we all enjoy language when we’re young. As we learn to speak, we often repeat single words or sentences almost hypnotically, sometimes drooling, delighted at the sounds. Later, nursery rhymes appeal to us in part for their language—their rhymes and their alliterations:

“Hey diddle diddle, the cat and the fiddle.”

“Goosy goosy gander/Wither will I wander?”

“Ring around a rosie/Pocket full of posey.”

When I was a child I thought the following tongue-twister was the height of cleverness, and I repeated it to myself again and again.

*

A flea and a fly in a flue

Were imprisoned, so what could they do?

Said the fly, “Let us flee!”

Said the flea, “Let us fly!”

So they flew through a flaw in the flue.

*

I still find it an ingenious little masterpiece.

I might have been especially sensitive to words because I spent two years in France, between the ages of three and five. When we returned to the states, I had to learn English all over again. At first, I hated its “watery” sound. No low “r’s” or throaty “n’s, no twisty “gn’s” as in “chignon.” But I got used to these deprivations and began to enjoy the special delights of English, such as compound words. Compared to French and Spanish (but not German!), English has an extensive range of compound words. Compound words can be nouns (toothbrush, bedroom, hairdryer, software); adjectives (red-hot, well-known, high-speed, old-fashioned); and verbs (babysit, dry-clean, house-hunt, water-ski). Perhaps compound words pleased me because of their efficiency.

I remember reading a kid’s book where some evil character got his “comeuppance.” I was thrilled. Not “just desserts” or “he had it coming,” but the elegant, ominous, slightly mysterious “comeuppance.”

Currently, my favorite compound word is “humblebrag,” first recorded less than 20 years ago. The word is succinct, self-explanatory, and very useful—because the phenomenon it names is so widespread. How did we live so long without “humblebrag”?

English has far more words than any other language, some 600,000, while Spanish has 93,000 and French, 60,000. A sizable proportion of this number is scientific, but English does contain massive numbers of words. Some French friends of mine were amazed by the plethora (“plethora”!) of words that English has for “sound”: tinkle and whistle and rumble and roar and whine and creak etc, etc. This was strange, delightful and difficult for them. It made it hard to learn the language.

Because each English word has its own shade of meaning and its own connotation, it is said that there is only one true synonym-pair in the language: “gorse” and “furze.” They both mean the same kind of bramble.

English speakers may have access to hundreds of thousands of words, but their active vocabulary, the words that come naturally to mind and that they sometimes use, is a mere 20-35,000 words: the same number of words used by Spanish and French speakers. As for the core daily vocabulary, or the words people use regularly, it’s only about 1000-5000 words for all three groups of speakers.

My core daily vocabulary might not be greater than that, but I do adore arcane new words and the jargon of professional fields, such as architecture or medicine. My windows have mullions (decorative strips of wood between the panes); my philtrum sometimes feels dry. The philtrum is the vertical fold between lip and nostril, which, according to Medline, is “believed to serve as a supply of additional skin to be recruited for oral movements requiring stretching of the upper lip.”

Even dry medical writing can yield verbal delight. When I read the word “recruited,” above, I had to smile. My philtrum spread.

But could I use the words “mullion” and “philtrum” in my active vocabulary? What would be the point, when I’d have to define them to most listeners? Aren’t words in the service of communication? So isn’t using an obscure word snobbish and somehow ridiculous? If you have to explain the word, what’s the point of using it?

If most people think “penultimate” is a word meaning “ultimate-ultimate” rather than its true meaning, “second to last,” should one really use it? Oh, but “penultimate” is such a delightful word! I hate to abjure it because many people are ignorant.

“Recruited!” “Mullion!” “Philtrum!” “Humblebrag!” “Penultimate!” “Abjure!”

Such are the pleasures of the word geek.

***

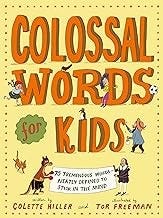

The love of words runs in the family. This month, my sister, Colette Hiller, published her second children’s book, Colossal Words for Kids, which has been extravagantly praised by The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post. The Daily Telegraph says, “Hiller stresses that her books are intended not so much to teach literacy as to install a love of language, to which end all the words are defined in playful and exuberantly illustrated rhymes, specifically designed to engage a child’s imagination. The definition of “volatility”, for example, will resonate with any young reader who has survived the playground: “When somebody is volatile / their mood just switches, like a dial: / at first they’re nice, then suddenly / they’re as mean, as mean can be.”

This follows the great popularity of Colette’s book, The B on Your Thumb: 60 Poems to Boost Reading and Spelling.

Note to midlife women: This is, by my count, my sister’s fourth career, following successful turns as an actor, a television producer, and a civic events impresario. She has three more children’s books under contract. Your life can pivot!

Hum...words, indeed dear Cathy, they are wonderful creatures, wonderful indeed.

love and hugs,

t

Thank you Catherine for this article that put a smile on my face. Also, I had a similar experience as a child when I spent two years in Germany from the age of 3 to 5. My father was in the French army, and we were there as part of the contingent of the French presence in Germany shortly after WWII. My two sisters were born there, and I had a German nanny. I ended speaking better German than French by the time we returned to France. I do not remember it, but my mother told me that I had to learn proper French all over again when I went to my French "kindergarten".